The Distances We've Traveled

Writer: Rachel Marston

Book Artist: Marnie Powers-Torrey

Rachel Marston’s fiction and nonfiction have most recently appeared in Sou’wester, Red Earth Review, and Black Candies, among other journals. She received her Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Utah. She is an Assistant Professor of English at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

Marnie Powers-Torrey holds an MFA in photography from the University of Utah and a BA in English and Philosophy from Boston College. She is the Managing Director of the Book Arts Program and Red Butte Press and an Associate Librarian. Marnie teaches book arts courses for the program and elsewhere. She is master printer and production manager for the Red Butte Press. Her favorite days are days at the press.

The Sacred Mountains of Home

Writer: Stephen Trimble

Printmaker: Michael Sharp

Space fills the West—exhilarating, unsettling space. “What we have instead of place is space,” says Wallace Stegner. Mountain peaks give us a focus in a land where the sky and prairie and forest are daunting in scale. Mountains break up that space and give it boundaries; they form the walls of the rooms—the lowlands—where people live and highways and railways pass through.

Most anywhere in the Rockies, we do not live in the mountains, we live at the foot of them—in towns or ranches built in deserts, plains, and valleys, in dry places dependent on mountain watersheds. Without water, people move on.

From these outposts we look across long horizons to where the moon and sun break over the rim of the earth, past silhouettes of nearby peaks. If we pay attention, the land begins to take on a familiar feeling. The proverbial "comforts of home" begin to include the landscape surrounding our warm houses—a panorama distinguished by landmark peaks.

Like many Westerners, I have moved from place to place. To make sense of my home, which has grown to include a major expanse of the West, I have borrowed the concept of sacred mountains from Southwest Indian people. While this may sound presumptuous for a non-Indian, to me it is humbling and nourishing.

To each Native American tribe the Creator gave a holy place bounded by mountains, one at each of the cardinal directions. Within the rough circle of land encompassed by these sacred peaks lay everything good, everything needed to live well. Indian people speak of the mountains overlooking their homes with reverence, affection, and awe.

I like this gesture of paying attention to the land.

After college, I lived in Tucson for a time, watching the moon set in a pastel pre-dawn sky beyond Baboquivari Peak, the great blunt stub off to the southwest that was the home of the Tohono O’odham creator, I’itoi. Baboquivari—wild chiles growing in its canyons, caracaras wheeling over its saguaros—stood for me as a sacred marker, a symbol of the power and soothing silence of the desert.

From Tucson, I moved to northern Arizona, to Flagstaff, and lived in the protective shadow of the San Francisco Peaks. A Navajo man, Steve Darden, spoke to me about these peaks, sacred to his people:

"That mountain has life. That mountain has a spirit. That mountain has a holiness.

“The Holy People live there. Because of that, it's a place where I can find refuge, rebirth. I garner strength from this mountain—spiritually, from this place."

I think of the Peaks from a distance, watching clouds build in summer monsoon season over the elegant angles of their dignified summits. I see the Hopi villages perched on mesas jutting like ship’s prows over the arid plateau country that sweeps away from bare sandstone and twisting junipers to the one snow-covered landmark in sight, the graceful curve of the San Francisco Peaks.

These 12,000-foot summits stand as beacon and promise. They reassure us with their life and lush fertility in a region known more for naked canyons and unnerving glimpses into geologic time.

They are the most holy mountains in the Southwest. Everything falls away from their summits. They stand at the center of the universe.

With a move to New Mexico in the 1980s, I lived in a Pueblo Indian landscape. My house in the Rio Grande Valley lay on the axis between Tsikomo at the summit of the Jemez, and Truchas Peak along the crest of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Pueblo people still make pilgrimages to shrines atop these sacred peaks, leaving offerings of cornmeal, prayer feathers, bits of bone and broken pottery.

I liked walking outside in the mornings to look up to the mountains and say their names: “Tsikomo. Truchas. Tsikomo.”

Truchas, with a gaping cirque on its face, rises to 13,102 feet, the second highest mountain in New Mexico. Tsikomo, a rounded dome on the rim of the Jemez caldera, has a distinctive meadow just below its peak, the only treeless patch on the western horizon.

“Tsikomo.”

After years of photographing in the Great Basin, my home runs westward, too—clear across Nevada, against the corrugated grain of basin and range, to the far rim of the desert. Here, Mount Rose stands as a sentinel above Reno, looking east over the dun and gray-green of playa and sage. Here my landscape ends.

Now, in Salt Lake City, I live beneath the Wasatch Front. Just over the shoulder of the first rise of peaks stands Mount Timpanogos, the dominant mountain of the Wasatch. Timpanogos is a Ute mountain, massive and commanding. I can feel it out there now.

Truchas, Baboquivari, Mount Rose, Timpanogos. These are my sacred mountains. Between them stretches my home. In the center place of this land stand the San Francisco Peaks, holy to all who dwell nearby.

As I journey across this land, I tick off the mountain ranges, anticipating the next landmark coming up from beneath the horizon. The roll of the hills takes me through the litany of life zones, up from desert grassland through piñon-juniper woodland and into fragrant ponderosa pines standing still and friendly in the sun. Or down through the concentric circles of desert shrubs—saltbush, greasewood, creosote—toward the austere playas that form the power spots, the chakras, of Basin and Range country.

Sacred prayers and dances mean profoundly more to Native people than they ever can to non-Indians. Within their beliefs, however, lies a teaching all can share. Indigenous people root their spirituality in landscape. Over and over, Native people have told me that the crux of their religion is simple: acknowledgment is the key, paying attention to the Earth and giving thanks for its blessings. To listen to the Earth, we need only relax and open our senses.

I write this in the house where I live, in the domain of Mount Timpanogos. I make pilgrimages, to walk the wildflower meadows of my sacred mountain of the north, to stomp through the first snow reaching down into the foothills to blanket the leafless oaks and maples.

I look out from Timpanogos to the four directions and dream out to the limits of my home.

* * *

Stephen Trimble lives in Salt Lake City, but he thinks of a big chunk of the West as home. He’s lived in the Four Corners states all his life. As writer, photographer, and editor, he’s published 25 books.

Trimble loves journeys across this home territory. He loves watching landmarks rise up from behind the horizon, loom importantly, and then pass by, to be replaced by new landmarks, new sacred lands.

Trimble’s website is www.stephentrimble.net. His Instagram, @stephentrimblephoto

Michael Sharp lives where the desert and the mountains meet, a place where landscapes intersect and blend in openly present geologic strata and form.

Sharp connects himself and his artwork to this place by using the intermedia that is the book arts. His Artist books are a place where the fibers of paper intersect and blend with the pigment in text and layered image.

Sharp’s website is: www.michaelsharpartist.com His Instagram, @sharpmg

Moss: A Love Story

Writer: Jodi Mardesich Smith

Illustrator: Kat Kinnick

One August weekend in the Uinta Mountains, something magical happened. Rain had already been falling for days when we pulled into a camping spot at the edge of a subalpine meadow at almost 10,000 feet. The constant rain thwarted some of our plans and kept us close to our trailer home base, but having to stay still, we got to witness something beautiful: what happens when water saturates this usually dry and rocky forest.

We got to watch the forest wake up. In an abundance of water, rock surfaces come alive with velvety patches of chartreuse and gray lichen. Fungi fruit and pop up through fallen pine needles. Tiny trumpets rise up from decomposing logs, and minuscule saffron-hued mushrooms pop out from woody crevices. And interspersed everywhere, connecting everything in these miniature fairy worlds, is moss.

Green, spiky clumps emerge from hidden slumber. In the presence of water, moss spreads its arms and stretches. Its cells expand and fluff, taking in and holding moisture (up to 20 times its weight) that can last it for months. That day, moss carpeted the entire hillside. It crept up the trunks of Engelmann spruces and lodgepole pines, reached over rocks, and especially fanned out near the edges of streams and lakes. The forest was a moss wonderland, and it became my happy place I have returned to again and again in the years since. No other visit has been quite so magical—each year since has been drier, with this past year Utah’s driest on record. I have seen more mushrooms within my terrariums at home in the past month than I saw all summer long in the forest. My meadow is just one snapshot, but it shows how increasing temperatures here are mirroring what’s happening across the globe.

Nature has always called to me. Before moss completely stole my heart, I cultivated patio tomatoes and backyard herb gardens. One of my earliest memories is of sifting through soil under a giant rubber tree in my backyard near the Southern California coast. Kneeling on the ground, parting the sparse grass, noticing tiny seeds and twigs. Beyond the colors and shapes my eyes saw, there’s a feeling of wonder. It’s a full body memory. But eventually nature’s whispers were harder to hear through the walls of home and school and eventually work.

Moss rekindled that connection. Moss called to me on city dog walks and stone cathedral steps. It drew me back to the mountains where I searched for it on rocks in mountain streams. I started carefully collecting small samples and watched them grow in glass containers. I learned from reading about 19th century botanical explorers that wrapping plants in moss greatly increased their chance of surviving long journeys from tropical islands, and it turns out that tucking small turfts of moss at the base of plants in a terrarium keeps them happy and helps helps these tiny ecosystems thrive. I learned that all kinds of creatures call moss home, and met stowaways, including tiny snails that snuck in on samples transplanted from parking lots and forests alike.

Once I realized I had been overlooking it for years, I longed to go back and see moss in all the places I had visited and lived. What spectacular mosses had I missed in the Puerto Rican rainforest, or on the streets of Paris and Montevideo? I also needed to know more about it. What is the purpose of this beautiful life form? Why does it exist?

Moss, it turns out, was the first plant to grow on land at least 400 million years ago. Moss evolved from filamentous green algae (which sounds so much more romantic than pond scum). It inched its way onto shores at the edge of lakes and streams, absorbing the moisture it needed to survive directly through its cell walls. It developed structures to collect and retain water from rainstorms, and spread where the wind carried its spores. It eroded rocks, prepared the soil, and paved the way for more complex plants with vascular systems, whose roots could reach deep into the earth for moisture and thus grow taller and live further from bodies of water. And because tiny, humble mosses were the first land plants to photosynthesize, they had an enormous impact on earth’s early atmosphere, taking in carbon and enriching our atmosphere with oxygen. The process of photosynthesis also transforms light and water into energy that feeds every living thing. In short, we owe our existence on our planet in part to moss.

If only moss could talk! What could it tell us about the first ferns and trees? Why has it stayed so simple, as other plants have evolved and grown complex? What could moss share about early reptiles and even dinosaurs? What came first, moss or tardigrades, the fascinating, almost microscopic eight-legged creatures that call mossy environments home but can survive outer space?

Moss was my gateway plant—the one that drew me in and made me curious about nature. Moss taught me that you don’t have to travel far to discover a new world.

Finding your own

Moss is virtually everywhere when you know where to look for it. Simply orient your body toward the north pole. Gaze toward the sun so that its east-west path is behind you, and turn around. Search for the north-facing wall of a garden, the shaded slope of an old house or barn, cracks in a tree-covered sidewalk, even on the north side of a track along a railway, and you might spot it—a patch of green.

Crouch down and look closer. What appears to be a fine velvet carpet is made up of tiny individual stems. If you happen to have a hand lens or loupe, you’ll discover the diversity. Thousands of moss species exist, growing in a multitude of shapes: low-lying, forked like ferns; taller upright strands with mop-like heads; star-shaped florets that grow in mounds like tiny cushions. When it dries out, it shrivels and goes dormant. If it has rained recently, it’s much easier to spot it.

If you happen to see some, tell us about it. Share your moss discovery stories and tag #mossalovestory so we can see the tiny worlds you find.

What is your moss? Is there something you suddenly noticed and realized it has always been all around you, waiting for you to discover it? Is there something that kindled curiosity in you that became an obsession?

* * *

Jodi Mardesich Smith is a California native transplanted to Salt Lake City. She is a writer, terrarium maker and plant caretaker. You can find her on Instagram at @jyotimedia

Kat Kinnick is a painter, printmaker, designer and illustrator living in Santa Fe. Often depicting wildlife, flora, and landscape of New Mexico, Kat works to create a culture of fondness and connectedness to the natural world. She is inspired by the magic and inexplicable nature of childhood, and many of her favorite artists are children’s book illustrators. She works with the intention of making fine art for adults and children alike. You can find her on Instagram @Katnikova and online at KatKinnick.com.

The Curious Conversation of Trees

Author: Brenda Sue Cowley

Artist: Stefanie Dykes

“We just moved here,” I say, to nearly every person I meet in this vast, tree-covered state of Washington.

Everyone is a stranger. Not just people...the actual trees.

Within the first two nights of relocating, I began hearing noises that sounded somewhat like far-away firecrackers, only to realize that it was a tree, soaked, giving up on its root system and falling. One falling tree would lead to others. And I kept listening. Trees so close to homes, but tall enough for King Kong himself to safely hide. Power lines. Cars. Houses. People.

I did not begin listening to what they were trying to tell me, because I grew fearful of the multiple ways these massive woods could cause real and present danger.

And in one, near direct hit, I learned instantly just what and why shouting the word “Timber!!!!” actually meant.

But there was often no warning, and I was too far from humans to be able to shout this word, alone, and in the woods.

Thus began my search for human connection.

“We moved from Utah,” I say, attempting to construct a comedic-scared look on my face.

Break the ice, girl.

“You may congratulate us, if you are so inclined,” I say.

The laugh, and the congratulations usually follow. Usually.

My heart is still in the desert, I think to myself, as I gaze at bodies of water, both large and small, in almost every direction I look. Forests and stand-alone and stand-together trees, in every direction I look.

There is water everywhere here, and I wonder if I was turning into a dusty, crumpled, lost piece of paper with only the smallest of scribblings – notes from the past– the type of piece of paper lost behind anchored furniture; the kind of thing one doesn't find or even remember, until one moves away from the desert– in search of water, forestry, wine, and willingness.

A conversation with a female stranger, in regards to living in a land of moisture, led to her giving me simple advice: “water and moisture just need space around them.”

At the age of fifty, I ponder this simple statement, as it seems to apply to so many things.

“Why did you choose to relocate?” This is the most oft asked question, and two hearts beat as we make up the answer and often reply with the easiest: “Family,” we say.

Heads nod in compassion, when we offer this answer.

One evening, a few months after the grueling relocation move, I found myself needing to take the train from Seattle to Olympia. I was alone, standing in the rain, soaked through, and disoriented in the dark, when I chose to speak to the man in the hat: “I just moved here,” I say. “Does this train go to Olympia?”

“Nohp,” he quips, and I see that glint in his eye that means friend to me. “It goes everywhere but Olympia. I suppose we could make the stop for you, however.” He smiled. I smiled. He gently supported my elbow as I carefully placed my foot on the first step leading up and into the train.

I found a seat, and because it was dark, I allowed the tears without fear of other passengers seeing me.

The man in the hat came back. He was wearing the uniform that says, “I work here.”

“This is my first train ride,” I say, hoping he doesn't see the liquid in my eyes.

“Mine too,” he jokes and walks away, checking on other passengers and adjusting the hat that makes him just barely too tall to do his job. I worry about his back, and how long it will take before he's grown crooked from having to bend down so often, and with so much attentiveness.

“We moved,” I say to my husband, and daily. These words are delivered at times robotically, a type of shock. The words, at other times are so sorrowful, my breath catches in my chest. And at other times– the most important times– the words are delivered with joy, a joy so profound, I begin to notice and feel the trees bend in our direction, welcoming us. The ferns actually waving a “hello!” to us.

I have found it to be a humbling experience to watch the trees bend and wave and whisper.

“No one knows us,” I say, and often.

The two of us stare at the Puget Sound and ponder how this water is healing wounds so deep, that strangers, friends, and even family often do not see nor remember the scars.

The trees have secrets here, and usually whisper at night. I've been listening in, feeling like I'm overhearing a private, but important conversation.

“It has to do with your root system,” they tell me. The trees are guiding me, and with such compassion. “Each one of us requires a different system of roots for sustenance.” The trees are teaching me. The trees now comfort and coo –they were brave enough to begin our conversation for me.

“We're new!” I now say, and often to anyone I meet. And that suffices to begin an exchange—tenuous at first—as so many seem to struggle in this year, 2018 --- talking. Listening. So many possible connections, dampened with fog, fear, perspiration...and hope.

“I can do this,” I say to the trees in the early morning hours now, while they're still seeped in conversation.

The trees lean in, releasing amber and pumpkin colored leaves, and droplets of moisture from the needles of the pines.

“Yes, you can.” The trees then gather, and lift the fog in one massive gesture of strength, to enable me to see what might be around the corner.

* * *

Brenda Sue Cowley had been living, professionally performing, writing, editing, small-business owning, delivering singing telegrams, and rescuing dogs in Salt Lake City, Utah, since 1991. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Brenda found her creative voice and community while living in Salt Lake City. In November of 2017 she and her husband (and their current beloved dogs), decided to hit “refresh” on Harstine Island for the year, while searching for a permanent residence in Olympia, Washington.

Brenda’s musical, “Shear Luck, the Musical,” in which she wrote book and lyrics, in collaboration with composer Kevin Mathie— received its world premier at the Grand Theater in Salt Lake City, in 2006. Other writing credits include, but are not limited to, “The Ladies of the Lake,” (in Slightly Peculiar Love Stories/Rosa Mira Books). You can reach her at: brenda.suesue(at)gmail.com

Stefanie Dykes is a co-founder of Saltgrass Printmakers. Saltgrass Printmakers is a non-profit printmaking studio located in Salt Lake City, Utah. Stefanie has taught at the University of Utah, Westminster College, and Snow College. She has been a resident artist at Anderson Ranch Art Center, PLAYA & Carrizozo Colony. Dykes received her MFA from the University of Utah, 2010. Saltgrass Printmakers was honored with The Mayor’s Artists Award in 2010. Stefanie was just selected as one of Artists of Utah’s “Utah’s 15 Most Influential Artists.”

Dykes has exhibited nationally: McNeese National Works on Paper; IPCNY; Ink&Clay; Harnett Biennial of American Prints; and internationally, Biennial of Douro, Portugal, DA3 at University of Central Lancashire and The Harris Museum, UK, International Print Biennale, Newcastle, UK, and has participated in International Print conferences: IMPACT10-Santander, Spain, IMPACT9-Hangzhou, China, IMPACT8-Dundee, Scotland and IMPACT6-Bristol, UK.

Stefanie Dykes

Saltgrass Printmakers

412 South 700 West

Salt Lake City, Utah 84104

www.SaltgrassPrintmakers.org

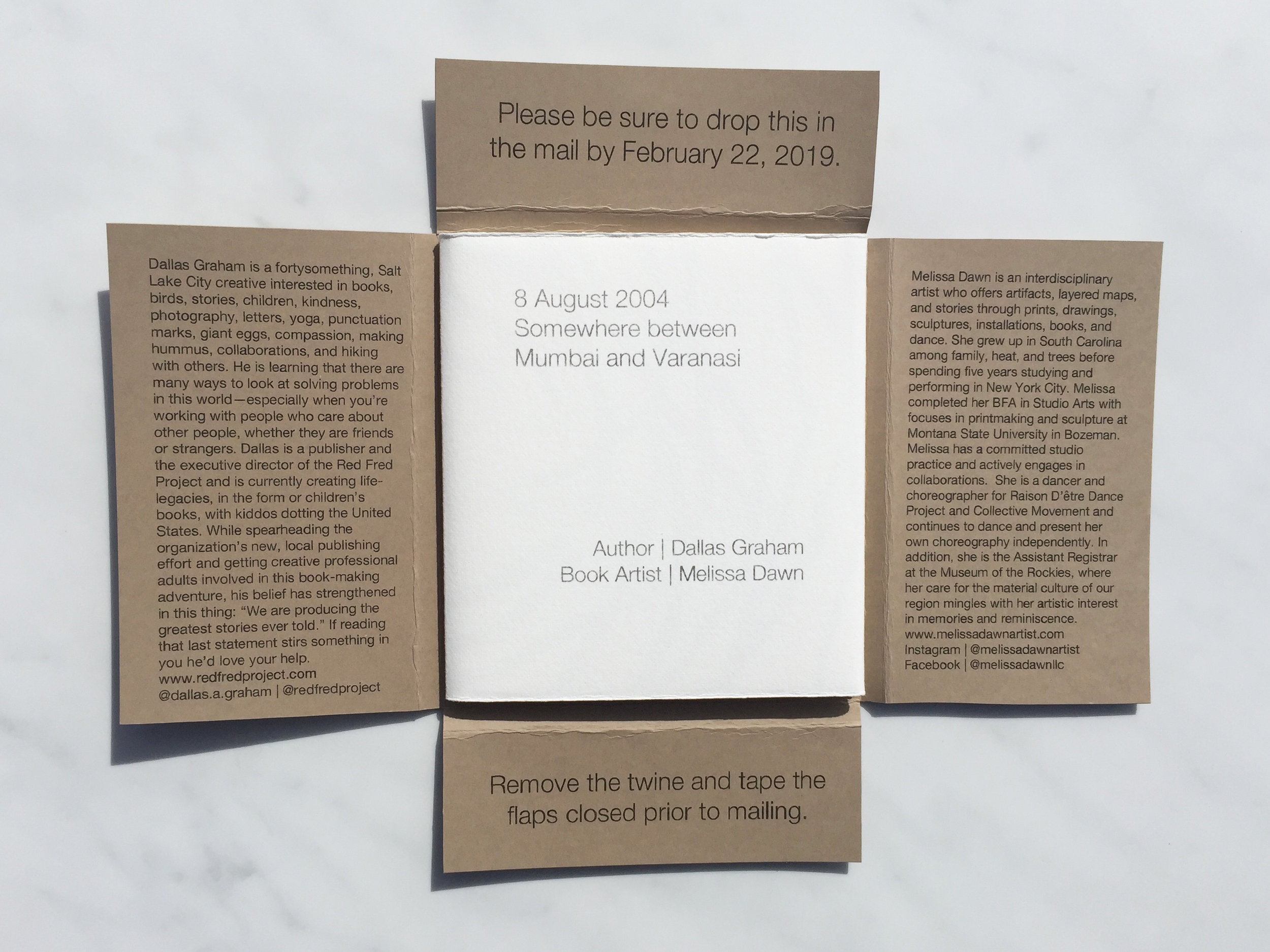

Somewhere between Mumbai and Varanasi

Writer: Dallas Graham

Book Artist: Melissa Dawn

8 August 2004

Somewhere between Mumbai and Varanasi

6:17pm and the flora passes at a glance. The circumstance is cinematic: a peacefully rocking passenger train with every-so-often conversations finding their way to my foreign ears. The metal wheels on the tracks and a small birthday party of two long-removed friends down the aisle jostles the air with creative impulse and timely pleasure. S remarks—constantly—on the perfectness of the scene. And happily, I concur. These evening hours harbor the light of day that doesn’t send you to bed or fill your blood with excitement too soon; this light of day resembles the same color back home—the color of sitting on a porch swing with a close friend and laughing about a memory 25+ years ago.

Where is paradise anyway? Milton said it was nowhere to be found; it was lost. Later he changed his tune and said it was regained—through a person. So, is Paradise a place or a person? It’s definitely subjective. I tend to think it’s always the better place (or person) where things are beautiful and scented with roses or coffee or cotton candy; it’s where fighting is kept to a few spats and where no one would ever consider the need of carrying a gun; it’s where dying isn’t possible because living is enjoyed too much. So, why it—in this moment—I feel so strongly about not deserving it? Deserving. Who is deserving of Paradise?

Time has been mercury, today. We boarded after the threats and the downpour at CT Station. The police officers paced like pit bulls looking for a fight. We spent 2 hours of restless sleep on the pavement, catching a couple of conversations with tourists from Minnesota.

Bally deserves it. He and his miraculous cab. As do the tens of thousands I saw through his windows—their faces and hands—THEIR FACES AND HANDS ON THE CAB WINDOWS. I’ve never seen anything like it. Really. People crawling to live. I couldn’t have pictured it without my eyes seeing it.

This train experience fits what I have borrowed from something, somewhere. (I’m sure it was NG.) We each paid around $35 for a 2-tier A/C ride, the alternative being packed into train cars that were simple wooden crates, filled with people that looked through the slats like cattle. Unexpected memories of Dachau stared me down.

“You live in Paradise.” Mr. Bally’s declaration to us. There are palm trees, alright, but they cling to the coasts. Fruits, vegetation, and even “tamed animals?” he asks. Yes. We even take them to our grocery markets. I know exactly what he’s talking about, more exactly than ever before.

Our sleeping situation was different at first: S and L were booked together and I was alone. But then the conductor was kind and did some rearranging so the three of us could be together. We occupied beds 14,15,16 and a fine fellow, going by the name of BS Meenah, was #13. Delightful. Smiling. An engineer. We all set to making the beds. (L is top left, D: bottom left; S: top right; BS: top right)

Is there order in Paradise? Yesterday, I saw a chaotic order so-rushingly-so that after a time, I didn’t mind the massive truck speeding straight for our rickshaw at 50+ miles/hour because I knew it’d stop one foot away. Order is keeping the children from being pulverized by cars when they are within feet of being struck. I know nothing of this organized chaos. Dabawallas—try that one on. Thousands upon thousands of unique, individual lunches delivered every day to their intended and never—NEVER—is a lunch pail lost or given to the wrong person. The miracle? The pail somehow makes it back to its owner’s home miles and miles away.

Once in a while a train going the opposite direction dragons by and I jump… like I just did. S giggled.

“Writhing in pain” never looked so perfect. Three men convulsing, rocking, yelling, soaked skin-through, to gain and ask for help. No eye contact. No efforts to reach out and touch. It was almost like chanting, now that I think about it. They were missing legs, their stubs mangled like old, tied-off bags of something left out too long without care. The positioning of their necks and heads remind me of the gargoyles of Notre Dame. Their rocking made my stomach turn. One man bore what once an arm, or the limb that developed instead of one, were two prongs of skin emerged where his elbow would be. Bally talked about the allowance of all types, but always: respectability of those that work hard for their living.

We went to bed pretty quickly, although I tried making light, “pillow-talk” with the kind stranger sleeping 5 ft from my body. (You should do that, right?) He is from Rajasthan, headed for Jabalpur, where we stopped to buy Shaun’s and Alexandra’s birthday gifts. That was about 12:15am.

The deaf remain blind to sound; the blind reach for the sounds of color.

BS has left. We have the compartment to ourselves. The food gifts from the “party” are still sitting next to me, nearly eaten. S and L are discussing the term “beggars.” I asked BS some questions and I’m sure I’ll get them wrong.

>>What is your name?

Tumharra Nam

>>Where is the toilet?

Saucalaya Kahaan hai

>>What time is it?

Kitne Baje Hain

>>Where is paradise?

Jahaan Svarg Hai

* * *

Dallas Graham is a fortysomething, Salt Lake City creative interested in books, birds, stories, children, kindness, photography, letters, yoga, punctuation marks, giant eggs, compassion, making hummus, collaborations, and hiking with others. He is learning that there are many ways to look at solving problems in this world—especially when you’re working with people who care about other people, whether they are friends or strangers. Dallas is a publisher and the executive director of the Red Fred Project and is currently creating life-legacies, in the form or children’s books, with kiddos dotting the United States. While spearheading the organization’s new, local publishing effort and getting creative professional adults involved in this book-making adventure, his belief has strengthened in this thing: “We are producing the greatest stories ever told.” If reading that last statement stirs something in you he’d love your help. www.redfredproject.com @dallas.a.graham / @redfredproject

Melissa Dawn is an interdisciplinary artist who offers artifacts, layered maps, and stories through prints, drawings, sculptures, installations, books, and dance. She grew up in South Carolina among family, heat, and trees before spending five years studying and performing in New York City. Melissa completed her BFA in Studio Arts with focuses in printmaking and sculpture at Montana State University in Bozeman. Melissa has a committed studio practice and actively engages in collaborations. She is a dancer and choreographer for Raison D’être Dance Project and Collective Movement and continues to dance and present her own choreography independently. In addition, she is the Assistant Registrar at the Museum of the Rockies, where her care for the material culture of our region mingles with her artistic interest in memories and reminiscence. www.melissadawnartist.com IG: @melissadawnartist, FB: 2melissadawnllc

Windows

Writer: Melissa Bond

Illustrations & Block Printing: Rigel Stuhmiller

Letterpress & Binding: Lemoncheese Press

The girl arrives in Costa Rica on a Thursday. It will be a time of windows and watching in a country of optimistic green and apathetic clocks. She does not own a hammock, but she will soon. She does not know how to sing but she will listen to the wind and she will travel through the night and song will find her.

She takes a taxi to a terrible hotel in somewhere San Jose. Mold walks across the tiled floor in the lobby and the men sitting on the low benches outside kick empty bottles, their eyes like rabbits. In her room, cockroaches skitter and hush and slide. At night, they are a blanket of sound tsk taking over the tile and across the headboard.

In the morning, she arranges her backpack. Water, iodine pellets, sleeping bag, camp stove, panties in a plastic bag at the bottom, journal in a plastic bag at the top, swim suit, knife, pens to write her way through. The girl washes in the sink, the hair on her legs curled gold. The sun of her life is high in the sky. It will burn. It will shoot through rainbows and tree limbs and the top of her head.

She is 23, lean and muscular, sundress a flaxen blue. The girl does not know but she is like an illuminated fish deep in the ocean, equipped with light organs. Those who see her do not forget.

At the entrance to the train station, she steps into a doorway and stops. She has not halted of her own accord, only realizes she can go neither forward nor back. She stares at the clock tick ticking. Her delicate hands reach back - the backpack is perhaps too wide for the doorway. Her fingers reach, pat the folds of backpack and twine around thick, calloused fingers that are pulling at the belt of her pack. The girl is unaware of the thieves that are rumored to carry razor blades with which to cut the pack belts off tourists. She only knows these surprised fingers, their stun at her twining around theirs - a moment of open curiosity - finger pad resting against finger pad. There is a liminal, quiet lean and then another man pulls the first and she is released into the swarm of bodies in the station.

Flash of a buttery smile, funnel of bodies, a ticket to Puerto Limón for two dollars. The train will come at seven, they say. Hands create a map in the air; this way, then that, past the bathroom with the broken sign, past the soda, a cafe with the darkest coffee. There, they tell her, there, their hands a kind of music. Not so far.

This line laid by Chinese, Italians and Hondurans will take eight hours to traverse. The girl will not be in first class with the aging baroque décor and tropical fruits laid out like seductive birds. She will ride in the cars with peeling paint and bodies fast together, fleshy and velvety, the talk a moving, bright tapestry.

The train pulls out, grabbing at the rails, mostly almost on time. The girl’s backpack is at her feet and she sits next to a tall man with impossible skin. He is her age perhaps, straight-backed, with skin like cream with a teaspoon of dark coffee. He radiates. Dark lashes caress the air like butterfly wings. They sit and lean. The train crawls through the jungle outside of San Jose. It stops to catch its breath. There is the sound of metal hitting metal. It moves forward again. At a station, hawkers strut onboard announcing their wares; mangoes, plastic bags of ice dribbled with a crimson liquid and yellow and green blossoms of popcorn. The man buys a bag of ice and dips his finger. He turns to the girl and presents his finger gone scarlet. She buys a bag of ice and together they turn each of all five fingers the color of rich blood. Neither of them speaks as the man, she has discovered, is from Argentina. She does not know his language, nor he hers but there is a new kind of language with this travel. It is hands and eyes and sugared ice and smiles that carry an ocean of meaning.

The girls sleeps and drifts. She has never felt this kind of rich aloneness. Her body is a page in a book that is being written. She watches the window of the train, click click clicking past fields of cocoa and maize and banana groves. A window of paradise red flowers appears and disappears. A window of steep mountain terrain, green enough to call itself a god.

And sometime after the mud and the riot of birds, after the sleep that closes and opens her, the man begins to sing. She wakes and listens. She can feel the warmth of his body, spine straight and loose. He is facing forward, his eyes closed. His song is neither loud nor soft. It is meant not for the air nor the passengers nor for her. It is a song sung for the man’s pleasure alone. A rosary, the girl thinks, the tenderness of his lips like a finger counting beads. He sings and smiles and they sway as the train moves toward the Atlantic. The girl has never seen a man sing like this before and the song gathers inside her like loam and seed, a song growing into an impossible whole, drifting inside of her with sonic weight. In Puerto Limón, she will carry her backpack to a beach with a breeze of blue and wild trees that makes her weep. And deep in the night she will unfold the song and try it in her mouth. A stranger’s gift; a thing she will carry.

* * *

Melissa Bond began her literary career in Salt Lake City 1995 by starting the city’s very first Poetry Slam, despite the death threats and the claims that she’d be escorted to the border for such heresy. In 2002, she won the Mayor’s Artist Award for the Literary Arts. In 2006, Melissa went first to Biloxi, MS and then New Orleans, LA to help tear out Katrina soaked drywall with her bare hands. She later helped put together a multimedia show about said drywall and the people that no longer lived inside it. During her tenure as Associate Editor and Poetry Editor of the Wasatch Journal, a glossy long-form magazine serving the Intermountain West, she was a finalist in the Western Publisher’s Association Maggie Awards for Profile writing. She’s published three chapbooks of poetry but only her friends and daring family members have read them.

For the past several years, she’s been working on raising a hilarious kid with Down Syndrome and another with the normal number of chromosomes, both of whom play a big part in her as yet unpublished book, Blood Orange Night. Her short film, Gooogled, based loosely on the book and mostly on her boy, premiered at the San Jose International Short Film Festival in October 2016.

Rigel Stuhmiller works in the Bay Area. She enjoys visual storytelling and being outside with her dog.

My Grandmother's Lessons:

Writer: Chantal V. O’Keeffe

Designer/Printmaker: Elpitha Tsoutsounakis

1. Ne pas se marier, avoir un amoureux.

The breath that left her mouth plumed toward the sky, smoke signals that punctuated the cold air and vanished. Behind them was the hulking metal ship she did not want to look back at, and in front of them-- everything. It was February 23rd, 1955. She had left the only home, life, and country she had ever known.

“J’ai froid,” her daughter said, a whisper of sound, no louder than the sound of a leaf falling to the ground. Their heavy winter coats were in a trunk, somewhere on a cargo ship at sea with all of their other belongings, set to join them in South Carolina in the next few weeks.

The movement around her-- of visitors, new arrivals, workers, family members, immigrants, vendors-- was fluid, but of a rhythm she did not recognize and was jarring. Someone from the French company that employed her husband was supposed to be meeting them, chauffeuring them to a train car, where they would spend the next two days before arriving in Charleston, South Carolina. Where she could once again begin crafting a new life. She could be anything and anyone she ever wanted.

She breathed in deeply, trying to get her bearings. The air smelled like burning rubber, and a layer of soot glimmered on the wood and stone. Ship horns sounded behind them. She could smell a trace amount of the rose and jasmine oil she had dabbed on her wrists, behind her ears, and on her clavicles before leaving the ship. The quietness of the floral scent calmed her.

They had arrived after spending 26 days at sea, the three of them sharing a tiny windowless cabin. Her legs were tight, all of her muscles were tight, and she ignored their instinct to flex and flee. A navy coat’s belt cinched her waist, covering a baby blue blouse tucked into a herringbone skirt, both of which she made herself. Those are the skills you acquire when you have 30 years of sewing experience and you are only 37. Her hair was the color of a wheat field and was freshly combed into tight ripples that framed her face. Her youngest was on her hip in a wool jumper a sister had made as a going away present. Her middle child was clutching her other hand, and the leather suitcase that had belonged to her father was tucked under her arm, held in place with the strength of iron will. Her oldest and only son was with her husband, waiting for their arrival in another state, which might as well have been an entirely different country.

2. Voyager.

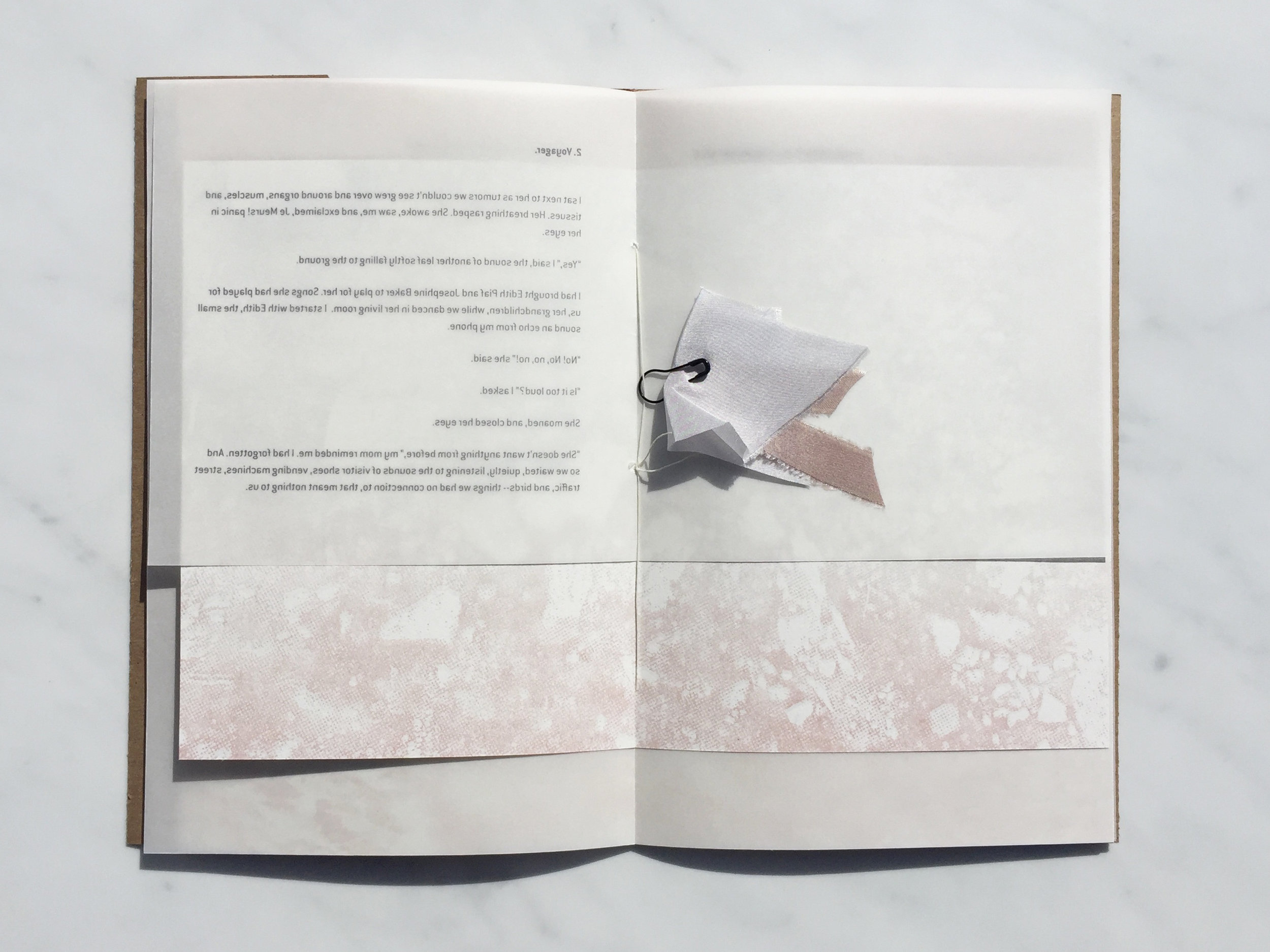

I sat next to her as tumors we couldn’t see grew over and around organs, muscles, and tissues. Her breathing rasped. She awoke, saw me, and exclaimed, Je Meurs! panic in her eyes.

“Yes,” I said, the sound of another leaf softly falling to the ground.

I had brought Edith Piaf and Josephine Baker to play for her. Songs she had played for us, her grandchildren, while we danced in her living room. I started with Edith, the small sound an echo from my phone.

“No! No, no, no!” she said.

“Is it too loud?” I asked.

She moaned, and closed her eyes.

“She doesn’t want anything from before,” my mom reminded me. I had forgotten. And so we waited, quietly, listening to the sounds of visitor shoes, vending machines, street traffic, and birds-- things we had no connection to, that meant nothing to us.

3. Gardez toujours votre indépendance.

Time had taught her that memory was not her friend. Memory reminded her of things she could not forget and things that were no longer possible. She preferred new things and new places. She liked the feel of her feet on fresh dirt; dirt that was clean and sanitary, and had not absorbed the blood of a loved one. Landscape that had no memory of her.

The sun was gone, but its glow remained on the snow, keeping the claim of nighttime away for a few more moments. The train sounded its horn before every approach through a small town. They passed homes that gave a silhouette’s glimpse into a life, like passing through a museum of shadow box dioramas. The three of them were in a private sleeper room, and after they cleaned up with a wash cloth, she put Edwige to bed and sat on the opposite bed, next to her petite chou, who was drawing trees with a pencil in a worn leather notebook her father had given her to documenter votre voyage.

The feeling of regret oozed like hot lava up her throat, and the only evidence of the rage inside of her was a clamped jaw bone that would eventually develop stress fractures, like bread crumbs left behind. The urge to scream at someone, anyone, was stifled by only her complete exhaustion.

He bragged that he had spotted her-- found her like a miner finds a gem and chips it out of the mine, look! Look at what I found. But she saw him first. She heard his narcissism and bravado gut the room, but she could feel his humanity, delicate and soft, and that was what she wanted. And so she cocked her hip, lifted her chin, and complimented his smarts, while teasing that it might be a match for hers. The war was over, and the overwhelming task of rebuilding had yet to become daunting. He fell for her, and she got everything she wanted, including what she didn’t.

Once the quiet set in-- both girls were asleep, and she was the only witness to that moment where day and night exist together-- she felt. There is not another way to explain this. The feeling she lived for, like an alcoholic who drinks to forget, she felt the release of jaw bones and clenched fists and muscles on the block, ready for the starting bullet. She had passed through four hours of America already, and there were no scorch marks on stones and mounds of rubble to walk over. There were no scars of war, no churches that had been bombed or basements that had hidden soldiers and friends who would die from rotting flesh. She saw no signs of resistance, no signs of trauma.

Looking into the blackness outside her window, she felt the return of possibilities. She felt the return of life, its pin-pricks of excitement and tiny bubbles of what-ifs coursing through the currents of her mind. This land, these places they passed through, it was nothing to her, and had no memory of her. She closed her eyes and drifted to sleep, the rhythm of the train taking her to a land where she had never existed before.

* * *

Chantal V. O’Keeffe studied writing at Hollins University and later California College of the Arts. She lives in Virginia and is finishing her first novel-- an historical novel about the previously unknown, now extinct, werewolves of the blue ridge mountains.

Elpitha Tsoutsounakis is a designer, printer, and Associate Director of the Multi-Disciplinary Design program at the University of Utah. In addition to client work, she maintains a studio practice in print as a speculative form of product and publication. Her academic research explores the role of design in our collective ecological consciousness and the experience of public lands.

Of Slugs and Carpetbaggers

Writer: Katie Wudel

Printmaker/Book Artist: Joey Behrens

Too often, I catch myself uttering that most banal of modern American refrains: "I need more hours in the day!"

But do I? When I have the rare blank slate of an unscheduled 24 hours to myself, I lapse into a routine that goes a little something like this: Wake up in the morning earlier than intended, scroll through Twitter for awhile until the dog forces me to get up and deal with his needs, make coffee, then head to the sofa, where I lay around looking at the internet until it's really too late, given the godforsaken traffic in LA (where I've chosen to live for some reason) to do much else.

"I'm a slug!" I'll say to my husband, or -- when he’s gone -- the dog. "Make me do something!" Though I wish I could attribute this vegetative state to self-care in our troubled times, I think it has more to do with laziness; bad habits; complacency.

But oh! When I travel! My slug persona dissolves as if sprinkled with salt! I expand, unfold, glow from within, becoming something more akin to a ball of light than an invertebrate. I'm all energy and movement, cramming adventures and tours and meals into every possible second of the day. When I went to Salzburg last fall for work, I had a free evening upon my arrival, in which I took a boat ride around the city, strolled through the city, climbed a mountain, ate dinner overlooking the Alps, and watched a Mozart concert in a medieval fortress. I also had a beautifully free day. I visited the small town of Fuschl, came back to Salzburg, ate a sacher torte at the hotel where it was supposedly invented, visited another small town called Hallstatt and ducked into its creepy hall of bones and walked across a tenuous bridge between two mountains while somehow managing not to faint from fear, came back to Salzburg, guzzled a brew from a mighty stein in Austria’s largest biergarten, got intentionally lost on the local university campus, and after walking 10 miles (and climbing 50 floors), I devoured some local stew and wine before falling asleep at 8 p.m.

What is it about exploring new parts of the world that opens us up to all that life has to offer? Usually such zeal for our precious time on earth is brought on only by the white light and/or dark abyss of a near-death experience. Sometimes I think the only way I'll ever live in the moment is if I become a permanent nomad, so that it’s impossible to settle in or feel truly comfortable.

I write this from another work trip in a different city -- New York. It used to be my home. There would be whole months when I lived here -- this famous magical urban place where everyone in the world longs to try and make it -- in which I had my eyes closed. Not literally, of course, but I could not bear to take in one more mariachi band on the subway, cranky cabbie making small talk, or pedestrian slammed by a car in the middle of the street. But over the last 48 hours, I've gone to a million restaurants and had a million drinks and seen a million friends, as if I'd arrived not by plane or Lyft but via Mary Poppin's carpet bag. This place is infinite for me right now, and every moment is alive.

By the time you read this, you may have forgotten the week when famous democrats in New York (along with the CNN offices) were mailed pipe bombs, and the midterms of 2018 still loomed. I do not know what your present looks like. But in the car that took me to dinner my first night here, my immigrant Muslim Lyft driver and I pondered our future. When I climbed in, he eyed my too-short hair and ruby red lips and brightly colored dress and cape and asked me, "What kind of artist are you?"

I told him that I'm a writer and a journalist, and laughed, and he said, "You're a kind soul. You Americans, all of you, you're so kind."

I laughed again, but this time more bitterly. I said it was hard for me to believe that, given the fact that colleagues in my industry had to evacuate from their office that very afternoon, in fear for their lives -- and that Trump was taking refugee children away from their mothers, ripping their hungry infants from their very breasts.

He said, "Trump doesn't hate those refugees. He wanted to scare other people from coming to America illegally. He only harmed a few for the benefit of many."

I couldn't believe it, the warmth which which he viewed a man who surely would hate him. I asked him what he thought about the bombs.

"I think they are sending bombs in the mail to warn people to be careful when shopping for the holidays, and to give people gifts in person. It's just a scare! Nobody's hurt! He wants us all to be kinder with each other."

We argued, fervently disagreeing about who we would've voted for in each other's elections. And then he drove up to the place where I was about to eat a warm delicious meal with one of my oldest friends, and he turned around. He gripped my hand.

"Enjoy your evening, friend. You deserve every happiness this world has to offer." And I told him he did, too.

* * *

Katie Wudel is the former deputy editor of GOOD magazine. Her writing has appeared in Prairie Schooner, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Tin House, Nerve.com, and many more publications, and she was granted a Hedgebrook residency for visionary women writers. Her Instagram handle is the absolute weirdest, but it rhymes with her last name a little: @noodlesploosh. Visit her website at katiewudel.com.

Joey Behrens lives with her partner Tony and sidekick Bistro (an overly enthusiastic rescue dog) in Wilkinsburg, PA, a small borough abutting Pittsburgh’s eastside. She strives to live a life that values curiosity, mysteries, and making. So far, the results of this endeavor include: a diverse body of work, two degrees, a smattering of obscure skills, and only minor injuries. You can see what she is up to by following her on Instagram @joey.behrens. Visit her website-that-sorely-needs-an-update at JoeyBehrens.com.

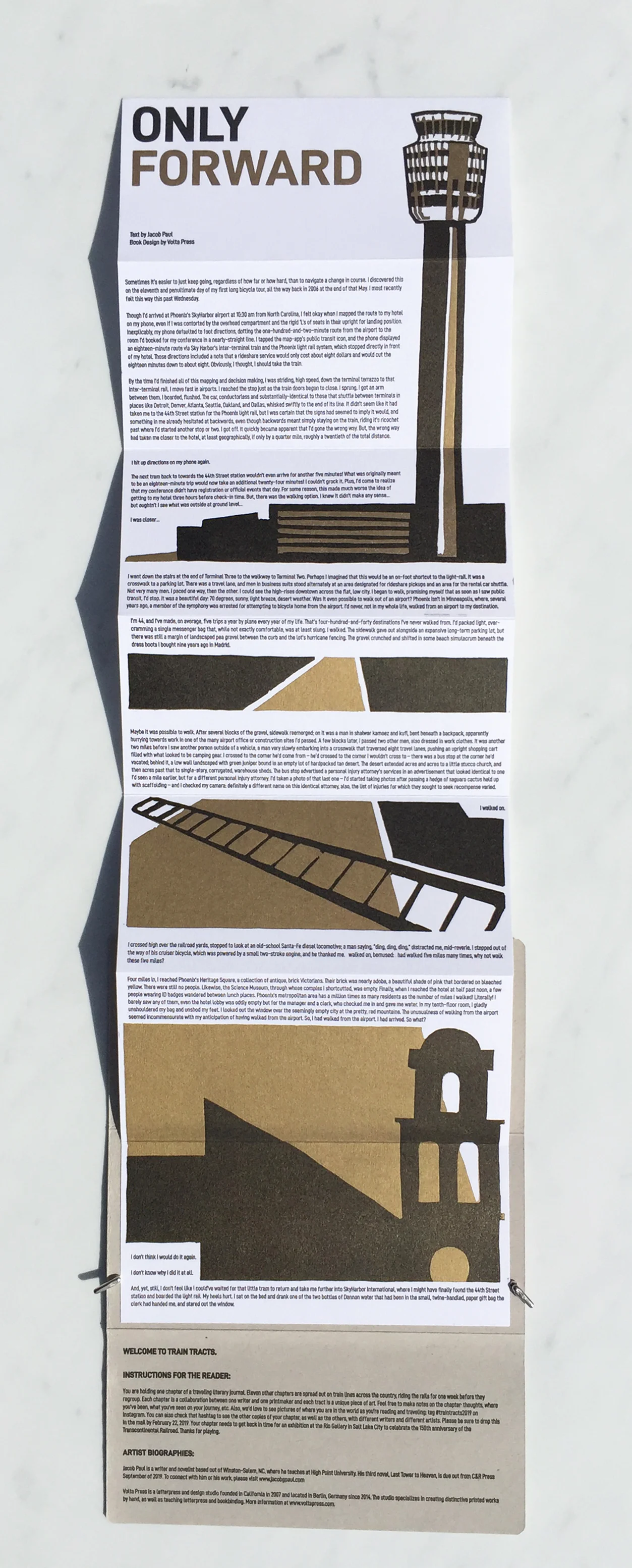

Only Forward

Writer: Jacob Paul

Design/Letterpress: Volta Press

Sometimes it’s easier to just keep going, regardless of how far or how hard, than to navigate a change in course. I discovered this on the eleventh and penultimate day of my first long bicycle tour, all the way back in 2006 at the end of that May. I most recently felt this way this past Wednesday.

Though I’d arrived at Phoenix’s SkyHarbor airport at 10:30 am from North Carolina, I felt ok when I mapped the route to my hotel on my phone, even if I was contorted by the overhead compartment and the rigid ‘L’s of seats in their upright for landing position. Inexplicably, my phone defaulted to foot directions, dotting the one-hundred-and-two-minute route from the airport to the room I’d booked for my conference in a nearly-straight line. I tapped the map-app’s public transit icon, and the phone displayed an eighteen-minute route via Sky Harbor’s inter-terminal train and the Phoenix light rail system, which stopped directly in front of my hotel. Those directions included a note that a rideshare service would only cost about eight dollars and would cut the eighteen minutes down to about eight. Obviously, I thought, I should take the train.

By the time I’d finished all of this mapping and decision making, I was striding, high speed, down terminal terrazzo to that inter-terminal rail. I move fast in airports. I reached the stop just as the train doors began to close. I sprung. I got an arm between them. I boarded, flushed. The car, conductorless and substantially-identical to those that shuttle between terminals in places like Detroit, Denver, Atlanta, Seattle, Oakland, and Dallas, whisked swiftly to the end of its line. It didn’t seem like it had taken me to the 44th Street station for the Phoenix light rail, but I was certain that the signs had seemed to imply it would, and something in me already hesitated at backwards, even though backwards meant simply staying on the train, riding it’s ricochet past where I’d started another stop or two. I got off. It quickly became apparent that I’d gone the wrong way. But, the wrong way had taken me closer to the hotel, at least geographically, if only by a quarter mile, roughly a twentieth of the total distance.

I hit up directions on my phone again.

The next tram back to towards the 44th street station wouldn’t even arrive for another five minutes! What was originally meant to be an eighteen-minute trip would now take an additional twenty-four minutes! I couldn’t grock it. Plus, I’d come to realize that my conference didn’t have registration or official events that day. For some reason, this made much worse the idea of getting to my hotel three hours before check-in time. But, there was the walking option. I knew it didn’t make any sense…but oughtn’t I see what was outside at ground level…I was closer…

I went down the stairs at the end of Terminal Three to the walkway to Terminal Two. Perhaps I imagined that this would be an on-foot shortcut to the light-rail. It was a crosswalk to a parking lot. There was a travel lane and men in business suits stood alternately at an area designated for rideshare pickups and an area for the rental car area shuttle. Not very many men. I paced one way, then the other. I could see the high-rises downtown across the flat, low city. I began to walk, promising myself that as soon as I saw public transit, I’d stop. It was a beautiful day: 70 degrees, sunny, light breeze, desert weather. Was it even possible to walk out of an airport? Phoenix isn’t in Minneapolis, where, several years ago, a member of the symphony was arrested for attempting to bicycle home from the airport. I’d never, not in my whole life, walked from an airport to my destination.

I’m forty-four, and I’ve made, on average, five trips a year by plane every year of my life. That’s four-hundred-and-forty destinations I’ve never walked from. I’d packed light, overcramming a single messenger bag that, while not exactly comfortable, was at least slung. I walked. The sidewalk gave out alongside an expansive long-term parking lot, but there was still a margin of landscaped pea gravel between the curb and the lot’s hurricane fencing. The gravel crunched and shifted in some beach simulacrum beneath the dress boots I bought nine years ago in Madrid.

Maybe it was possible to walk. After several blocks of the gravel, sidewalk reemerged; on it was a man in shalwar kameez and kufi, bent beneath a backpack, apparently hurrying towards work in one of the many airport office or construction sites I’d passed. A few blocks later, I passed two other men, also dressed in work clothes. It was another two miles before I saw another person outside of a vehicle, a man very slowly embarking into a crosswalk that traversed eight travel lanes, pushing an upright shopping cart filled with what looked to be camping gear. I crossed to the corner he’d come from – he’d crossed to the corner I wouldn’t cross to – there was a bus stop at the corner he’d vacated; behind it, a low wall landscaped with green juniper bound in an empty lot of hardpacked tan desert. The desert extended acres and acres to a little stucco church, and then acres past that to single-story, corrugated, warehouse sheds. The bus stop advertised a personal injury attorney’s services in an advertisement that looked identical to one I’d seen a mile earlier, but for a different personal injury attorney. I’d taken a photo of that last one -- I’d started taking photos after passing a hedge of saguaro cactus held up with scaffolding – and I checked my camera: definitely a different name on this identical attorney, also, the list of injuries for which they sought to seek recompense varied.

I walked on.

I crossed high over the railroad yards, stopped to look at an old-school Santa-Fe diesel locomotive; a man saying, “ding, ding, ding,” distracted me, mid-reverie. I stepped out of the way of his cruiser bicycle, which was powered by a small two-stroke engine, and he thanked me. I walked on, bemused: I had walked five miles many times, why not walk these five miles?

Four miles in, I reached Phoenix’s Heritage Square, a collection of antique, brick Victorians. Their brick was nearly adobe, a beautiful shade of pink that bordered on bleached yellow. There were still no people. Likewise, the Science Museum, through whose complex I shortcutted, was empty. Finally, when I reached the hotel at half past noon, a few people wearing ID badges wandered between lunch places. Phoenix’s metropolitan area has a million times as many residents as the number of miles I walked! Literally! I barely saw any of them, even the hotel lobby was oddly empty but for the manager and a clerk, who checked me in and gave me water. In my tenth-floor room, I gladly unshouldered my bag and unshod my feet. I looked out the window over the seemingly empty city at the pretty red mountains. The unusualness of walking from the airport seemed incommensurate with my anticipation of having walked from the airport. So, I had walked from the airport. I had arrived. So what?

I don’t think I would do it again.

I don’t know why I did it at all.

And, yet, still, I don’t feel like I could’ve waited for that little tram to return and take me further into SkyHarbor International where I might have finally found the 44th Street Station and boarded the light rail. My heels hurt. I sat on the bed and drank one of the two bottles of Dannon water that had been in the small, twine-handled, paper gift bag the clerk had handed me, and stared out the window.

* * *

Jacob Paul is a writer and novelist based out of Winston-Salem, NC, where he teaches at High Point University. His third novel, Last Tower to Heaven, is due out from C&R Press September of 2019. To connect with him or his work, please visit www.jacobgpaul.com

Volta Press is a letterpress and design studio founded in California in 2007 and located in Berlin, Germany since 2014. The studio specializes in creating distinctive printed works by hand, as well as teaching letterpress and bookbinding. More information at www.voltapress.com.

Of Pregnancy, Strangers, and Pilgrimage

Writer: Emily Dyer Barker

Printmaker/Book Designer: Rachel Melis

Sylvia Plath ends her nine-line poem “Metaphors” with this sentence: Boarded the train there’s no getting off. She doesn’t place a comma between train and the option of leaving because there is no comma there in real life either. No pause, no stylistic resting of voice or image, just a run-on mass of energy barreling down to the period stop.

*

The first time I saw my daughter’s face, I was shocked I didn’t recognize it. I couldn’t recognize it—I’d never seen her before, but I suppose I thought there would be a spark of some kind of recognition. I’d been carrying her with me for nine months—she’d been everywhere, heard everything with me. She’d been poking me and shaking me each morning for the last four months. Now, presented with her face for the very first time, I thought: There is her face.

*

On a flight to Venice, I sat next to a woman who told me about her twin boys. She kept saying over and over how she breastfed them, and then how she pumped, how she worked so they could have breastmilk until they were 18 months old. It was immense—the strategies, the hours, the effort it took to transfer the milk from her body into theirs. She told me they were going to college that summer. She couldn’t believe it—They’re going away now. Then she told me they were part of a quadruplet set. Two embryos had split creating two sets of identical twins. At 29 weeks, they were all born, and two died—one from each split embryo. She told me all of their names. She told me the two who died were buried in a cemetery close to her house.

*

Other metaphors Sylvia uses: a riddle, an elephant, a house, a melon walking, bread rising, money in a purse, a stage, a means, a calving cow. These are all accurate, but I think a lot about how I haven’t boarded a train, I am the train—carrying a stranger to a period stop that I can’t control.

*

I can remember only a few things about the woman who told me about her sons—the twins. She had freckles on her chest, where the neck meets the breast bones. These bones looked like wings of birds. Her hair was soft and light—each strand existed on its own. Her face was intense like the desert.

*

I’m pregnant again and I cannot explain the intense strangeness of being in this state, to carry an entity which isn’t me. At seventeen weeks, the fetus announced himself with three soft taps on my uterus. So kind! So polite. When he hiccups—both rhythmic and abrupt—I’m the only one who can feel it.

*

Dr. Holmgren just happened to be the doctor assigned to my c-section for my daughter’s breech birth. She said a few words to me before the surgery, but I can’t remember what she said and I couldn’t describe what she looked like to anyone. At my son’s anatomy ultrasound consultation, she walked in the door and I immediately knew it was her. She pulled my daughter from my body, and now she was pointing to this new baby’s brain, his heart, his liver, discussing the way his blood was moving through his body—checking on the position of the placenta—the only organ we share.

*

I don’t know the name of the anesthesiologist who attended the surgical birth of my daughter. He stood on my right side and watched with me as she emerged from my body. He made jokes and kept me alive.

*

At 28 weeks, I can’t help but think about the pilgrimage of a body passing through another body—it changes the way I think about the phrase, Walking the earth. We must all pass through a body to see the ocean—to see the sky.

*

The bodies that pass through us, stay with us. Even in the event of an early miscarriage or still birth—women carry the DNA of all their children in their bloodstream.

*

When my daughter was born, I felt as if I had been given a baby that could have been anyone’s baby. She could have come from anywhere in universe, a stork with a pink polka dot bag in its beak, a park bench, a cave, a river, any other woman’s body: she was a stranger. I didn’t feel like she was my daughter. But I did feel a deep, chasm of responsibility for her. It felt like a relief. Like, Oh this—this is bread. Let this nourish you.

* * *

Emily Dyer Barker’s artist books have been exhibited nationwide and archived in various special collections libraries. Her fiction and poetry has been published or is forthcoming in Tar River Poetry, Connu, and Hayden’s Ferry Review. She is currently in the creative writing PhD program at the University of Utah and the managing editor for Western Humanities Review. You can follow her projects @emidyerbarker on Instagram.

Rachel Melis is an Associate Professor of Art at the College of Saint Benedict & Saint John’s University in Minnesota. She received her MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Rachel’s prints, books, and installations have been exhibited across the country and abroad. Her current work compares motherhood to natural cycles of carrying, caring, and letting go of control. You can follow her press, @Greenleafline, on Instagram and at rachelmelis.com.

8 Kinds of Light on Western State Lines

Writer: John K. Peck

Printmaker: Kim Van Someren

Jackpot, Nevada (southbound)

The Great Basin Highway cuts a straight north-south line through dry scrub and shale. Sunrise and haze on the left, unbroken blue on the right. Dead coffee smell in the van’s cool interior, whirr of a tired engine, brilliant star-shaped crack on the windshield.

The clatter of cheap steel bells on a metal-glass door. “North or south?” “South, all the way through.” We both smile. Pouring burnt coffee into a large plastic mug, its blue plastic interior baked by the dark, acidic brew of ten states.

Pine Bluffs, Wyoming (eastbound)

Dark auroras of endless cloud cover above, with patches of brilliant yellow-white sun punctuating the fields below, as if sunlight were just another crop, something that could be coaxed from the ground. Waving waist-high plants, heavy with fallen rain.

A rainbow fading from light to dark against the welling clouds, impossible, yet persistently there, passing slow as a leviathan in the darkening sky.

Clovis, New Mexico (eastbound)

With auburn hair and tawny eyes

The kind of eyes that hypnotize me through Hypnotize me through

A massive squall of static, almost demonic, blares as lightning pops blindingly across the night sky. In the still moment after, with spidery cracks of light still painted on our retinas, the song returns, now small and tinny. A quick glance across the space between seats, then the world-ending boom of thunder breaking in the atmosphere.

Monida Pass, Montana (southbound)

Those of us in the back have been drinking, and there are fry boxes and burger wrappers on the floor. We got some Everclear and mixed it with something, maybe an Icee, doesn’t matter.

The dark outside reflects in our black, smiling eyes.

From here, south or west doesn’t matter, you’ll end up in Idaho. Like when a ship goes under: port or starboard, rich or poor, you’re going in the water.

Wendover, Utah (eastbound)

The sight is biblical, or Neptunian maybe: plains of endless white, building in monochrome intensity as the low mountains at the state line fade in the rearview. A padded room, where minds can do some bouncing around, test their own elasticity. Driving east, looking at the faces of the westbound, sometimes eyes meet, as if to say why this zero-sum game? What if, next time, we just stayed put and let things work themselves out?

East Blythe, California (westbound)

“I work in Yuma, 90 miles away. So my commute is about an hour and a half. About the same as working in the city and sitting in traffic all morning.” He smiles. A few hundred feet off, a breeze shakes a willow over the Colorado, its leaves flickering in the sun. The red paint on his truck is faded but the chrome glints. His terrier sits on the passenger seat, sniffing at the thin diesel-tinged air.

Sweet Grass, Montana (northbound)

Hills of dry grass rise and fall under our tires like slow, rolling waves. The sun is hidden behind a blank white sky, the light not really doing anything, just hanging there. A sudden, black cloud of songbirds rises, pulsing amoeba-like into the sky before settling back into distant fields.

The Canadian border lies ahead, passing invisibly through dirt and water, through blades of brown grass and chattering songbirds. Wire-thin and faint on the map, a municipal divider dotted with drayage warehouses and blocky checkpoints.

Someone turns the radio off.

Virginia Dale, Colorado (northbound)

Too much time spent on interstates makes avoiding them an urgent task. The vast sameness, the numbered exits with identical chains, the reeking feedlots and blank steel warehouses: trading the slow meander of grass and hills for a dead-straight line of gray.

Here, in this lone lost capillary, the rocks rise like jagged pagan chimneys. The light is a sort of red-hued blue, impossible but true. A bird flits past, quick as a blink, as we wind ourselves deeper into the landscape.

* * *

John K. Peck is a Berlin-based writer, printer, and musician. His work has appeared in Salon, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Jubilat, VOLT, SAND, and anthologies such as The Best of McSweeney'sInternetTendency andStoriesFromtheCity:ASlowTravelBerlinAnthology .He is the editor of Degraded Orbit (degradedorbit.com) and co-founder of Volta Press, a letterpress studio that started in Oakland in 2007 and opened in Berlin in 2017. www.johnkpeck.com IG: instagram.com/voltapress

Kim Van Someren is the Instructional Technician in Printmaking, Painting + Drawing and IVA at the University of Washington. She holds a MFA in Printmaking from the University of Washington (2004) and a BA from the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse (2002).

She has taught Printmaking at Pratt Fine Arts Center, Kirkland Arts Center, the Frye Art Museum, the Seattle Arts Museum, and University of Washington.

Van Someren has exhibited locally and nationally; her work included in several collections including the New York Public Library, the University of Iowa, the University of Washington and Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Van Someren is represented by Bridge Productions, Seattle, Washington. https://www.bridge.productions/

www.kimvansomeren.com

The Last Time I Was Afraid to Fly

Writer: Amie Tullius

Book Artist: K Stevenson

I didn’t really think the young man was a terrorist, but I’m embarrassed to say now that the thought crossed my mind. He did seem to be deeply uneasy, his hoodie up, his leg bouncing, and his gaze darting around the Southwest gate as we waited to board the plane from Oakland to Long Beach.

This was just a little over a month after the 911 attacks, and to be fair, we were all deeply uneasy. In those emotionally ragged days I felt suddenly and shockingly vulnerable. And while that feeling of vulnerability made some people want to flee to Canada, and others to buy semi-automatic weapons, the only thing that I felt might keep me safe was love. I think I hoped that if I could spot danger early enough I might somehow be able to diffuse and decommission it with my love.

I sat down next to the restless-leg kid, one empty seat between us. He glanced my way as I sat.

“How’s it going?” I said, meeting his eyes and giving him a smile.

“Okay,” he said.

Every day for the past month I’d been driving past soldiers carrying

machine guns on my commute over the Golden Gate Bridge. The news was full of stories of deadly powders being sent in the mail, and everyone seemed full of speculations and creative ideas for what the next attack might be. The aftermath of the attacks on our country had left us with an electrical storm of anxiety.

“Are you going to visit family?” I asked. I wondered what the symbols tattooed on his knuckles meant.

“Yeah,” he said. He seemed maybe a couple years younger than me, 22, 23, perhaps. “You?” he asked, and his leg paused in its bouncing as he waited for my answer.

“Yes. Well... sort of,” I told him. I was meeting up with my boyfriend for Thanksgiving, I said. We were going to his grandma’s house, and I was meeting his family for the first time. I was nervous about that. I laughed; it was such a wholesome thing to be nervous about. The boy laughed and commiserated. He told me he was going home for the holidays, too, to his mom’s house in Orange County, where he’d grown up.

“My sister has a new baby I haven’t met yet,” he said. “So I’m going to meet my new nephew. I didn’t want to go,” he said. “I’m just... I’ve always been afraid of flying and now… It’s just so messed up.”

“It’s so messed up,” I agreed. “Oh, but, congratulations on your baby nephew!”

Yeah, thanks!” he said, “Wow, I mean, I have to go home, right?” When he smiled his whole face opened up. He seemed like someone I might have grown up with, known my whole life.

* * *

On the plane I chose a window seat. Outside the sun was low over the tarmac. A kid with a kind of hip hop vibe settled into the center seat next to me. He was wearing big white headphones and I could hear the faint buzz of his music through the foam.

The engines started up, and the cabin filled with the smell of jet fuel, perfume, and hair products. I turned on my little air nozzle.

I told myself I’d be fine. It would be fine.

I thought about the passengers on those other planes, and how their flights had started out just like this, with babies crying and the fasten seat belt lights on. In some way we’d all been on the planes that hit the towers.

We built up speed and I felt the wheels leave the ground. The plane surged its way into the air, bumping and jostling. The baby cried louder in hiccupy protest, the air felt thick, and I had that heavy gravity wooziness of take-off. I looked out toward the city, out the little window. The sunset was reflecting off the skyscrapers.

And then quite suddenly the pressure in the plane lifted and it was if we were floating. We were so, so very light. We were gliding up into the sky, above the gleaming city with its twinkling expanses of bridges, and in that moment the world became exquisitely sublime.

The cabin lights in the plane were soft. My fellow travelers were illuminated in the warm spots of their reading lights, rows and rows of backs of heads that suddenly seemed so dear. A woman a few seats up from me was wearing a fuchsia t-shirt. I mean: wow. Fuchsia! We live in a world with fuchsia! Her hair was pale gold with a wave of bangs that crested four, five inches above her forehead. I loved the crying baby, the young tech executives, the woman in a teal and silver sari diagonal from me opening and closing her mouth-- trying to help her little boy to get his ears to pop.

Since that evening I have heard of other people having similar experiences, where some switch in the brain suddenly flips from terror to bliss. Not only did I not feel scared anymore, I felt a kind of ecstasy and the most immense appreciation for whatever sliver of existence I got. If the plane went down now, fine, I thought. Everything beautiful ends and who am I to be greedy about it? I felt fiercely in love with the world. But love didn’t feel like anything that would keep me safe. If anything love made me feel more vulnerable; life felt precious, brief, and extremely fragile.

It was hard to imagine ever not feeling the immense waves of gratitude I was experiencing. It was impossible to imagine that everyone else on the plane wouldn’t be having exactly the sensation of the heartbreaking ecstasy of existence that I was experiencing.

The guy next to me glanced up from his Maxim magazine and then shook his head, grinning at my expression.

I wondered if somehow this buoyant feeling had been triggered by the friendship I’d struck up with that scared stranger I normally never would have sat next to. I opened my mouth to say something to this other stranger sitting next to me, to marvel at the world, at the night, at the great wonder and improbability of us existing at all. I was smiling, almost on the verge of tears. “I mean: can you believe this?” I wanted to ask him.

“Aw,” my seatmate said, lowering his headphones to his neck and looking me up and down. “You’re cute. What’s your name?”

“I’m… um...” I said.

And, like that, my unexpected bliss fugue was broken. I laughed and introduced myself to my seatmate. Then I pulled myself together, folded myself back up, and turned to the window to let the luminous cobalt and aqua of twilight wash over me.

* * *

Amie Tullius is a fiction writer, art writer, and essayist. Her work has been published in a smattering of publications around the West. her artist books have shown in Salt Lake City and San Francisco, and she has an exuberant curatorial streak that leads her to do things like organize peripatetic literary journals that she sends traveling the country on trains. She is working on her first book. IG: @amietullius, www.amietullius.com

An artist and educator, K Stevenson is a resident of Utah, though originally transplanted from Minnesota— very near Lake Wobegone, to be more precise. She currently directs Printmaking in the Department of Visual Arts and Design at Weber State University, Ogden, UT. When not working— in the studio or at school— she tries to be in the beautiful, but demanding, geography of the Intermountain West— doing as much of nothing as is possible.

She can be reached via e-mail at: kstevenson1@weber.edu

K is most grateful for:

Printmaking assistance from Amanda Joy, printmaking technician extraordinaire; DOVAD, Department of Visual Arts and Design, Weber State University; Ogden, UT.

Occasionally, Amanda’s family might think she loves printmaking more than them.

They might be wrong.